JOb Market paper |

My first authored working papers and publications are described below, with links to the full papers (if available). My full CV is available here.

|

|

“Prospective Outcome Bias: Incurring (Unnecessary) Costs to Achieve Outcomes That Are Already Likely,” invited for minor revisions at Journal of Experimental Psychology: General (with Joe Simmons).

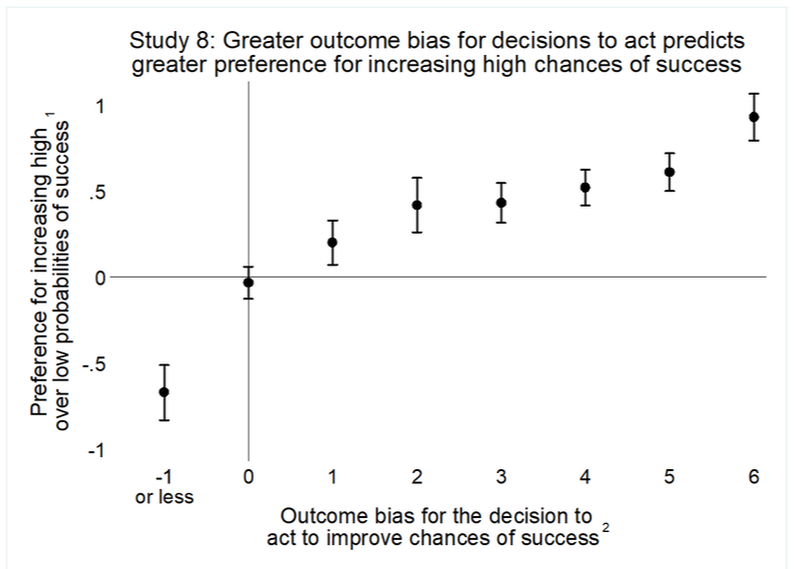

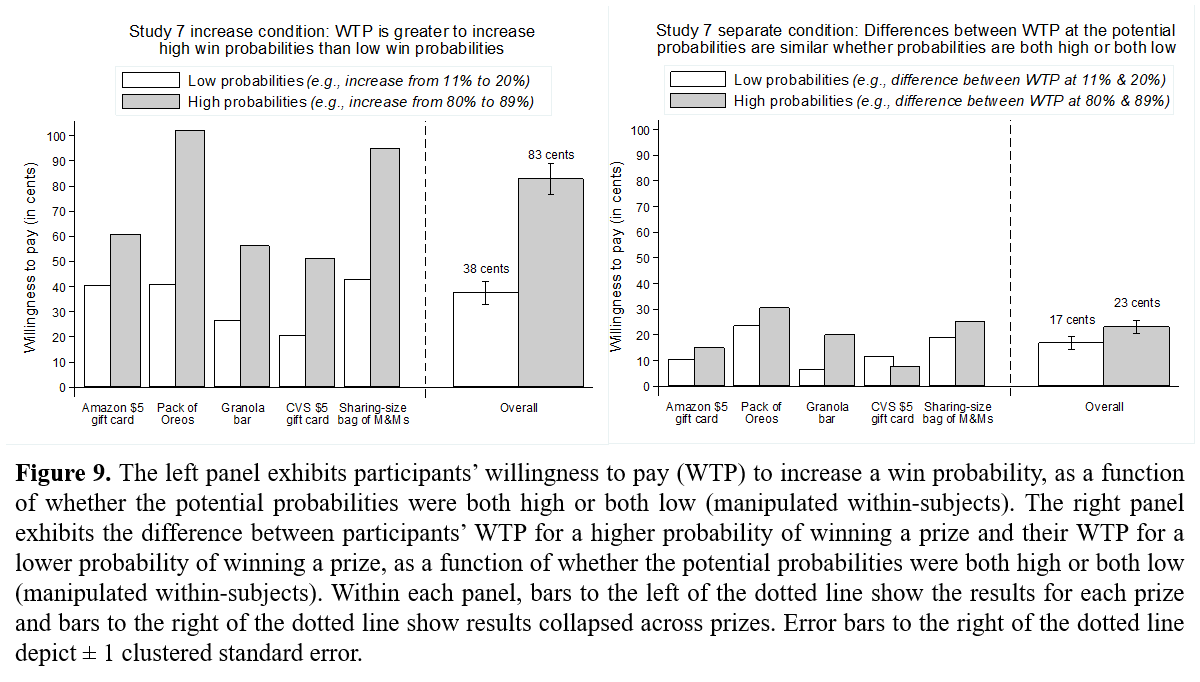

Question: When do consumers overspend on products that improve their chances of success? Summary (not abstract): Often, people buy products not because of the product's intrinsic value, but because they hope that the product can improve their chances of attaining some goal. For example, people buy fertility drugs to increase their chances of conception, not because they intrinsically like fertility drugs. It is hard to decide how much to spend in this circumstance, because the decision depends on many more factors than one's intrinsic valuation of the product. However, in hindsight, people usually deem this kind of expenditure to be justified when they meet their goal, even if the expenditure itself doesn't make any difference. Consequently, people tend to overspend on products that increase their chances of goal attainment, especially when (1) their chances were high to begin with, and (2) when the stakes are high but the impact of the product on the chances of success is very low. |

Publications & papers under review

|

“Extremeness Aversion Is a Cause of Anchoring,” Psychological Science, 30(2), 159–173 (with Celia Gaertig and Joe Simmons).

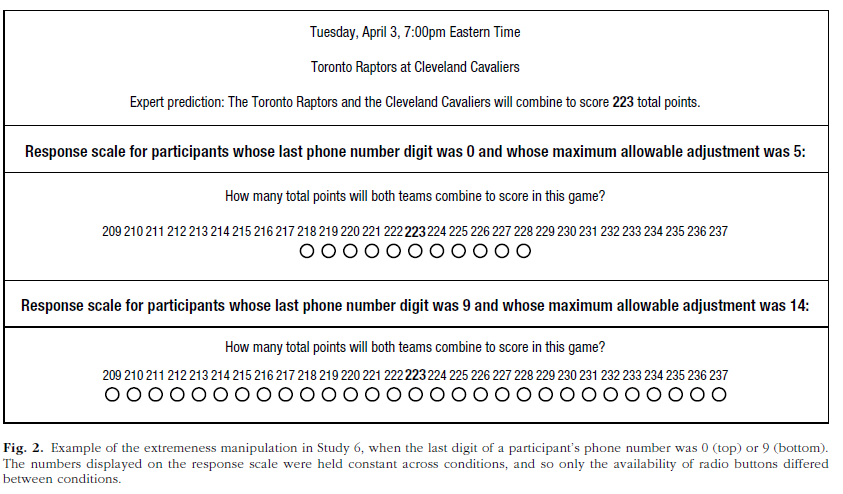

Question: Is anchoring caused by consumers' aversion to making extreme judgments? Summary (not abstract): People are often averse to making extreme judgments, and this bias helps to explain "anchoring effects". For example, consumers are reluctant to give a valuation of a product that is too far from an irrelevant-but-salient anchor value (such as a list price), because such a judgment would feel extreme. In addition, people are particularly averse to making judgments towards the edges of (or outside of) arbitrary ranges. Thus, marketers could potentially increase purchases at sales prices by indicating a range of higher Recommended Retail Prices (RRP) rather than a single higher RRP. For example, telling customers, “RRPs range from $100-$110, but you can get it for $50!” may be more effective than telling customers, “The RRP is $110, but you can get it for $50!”. |

|

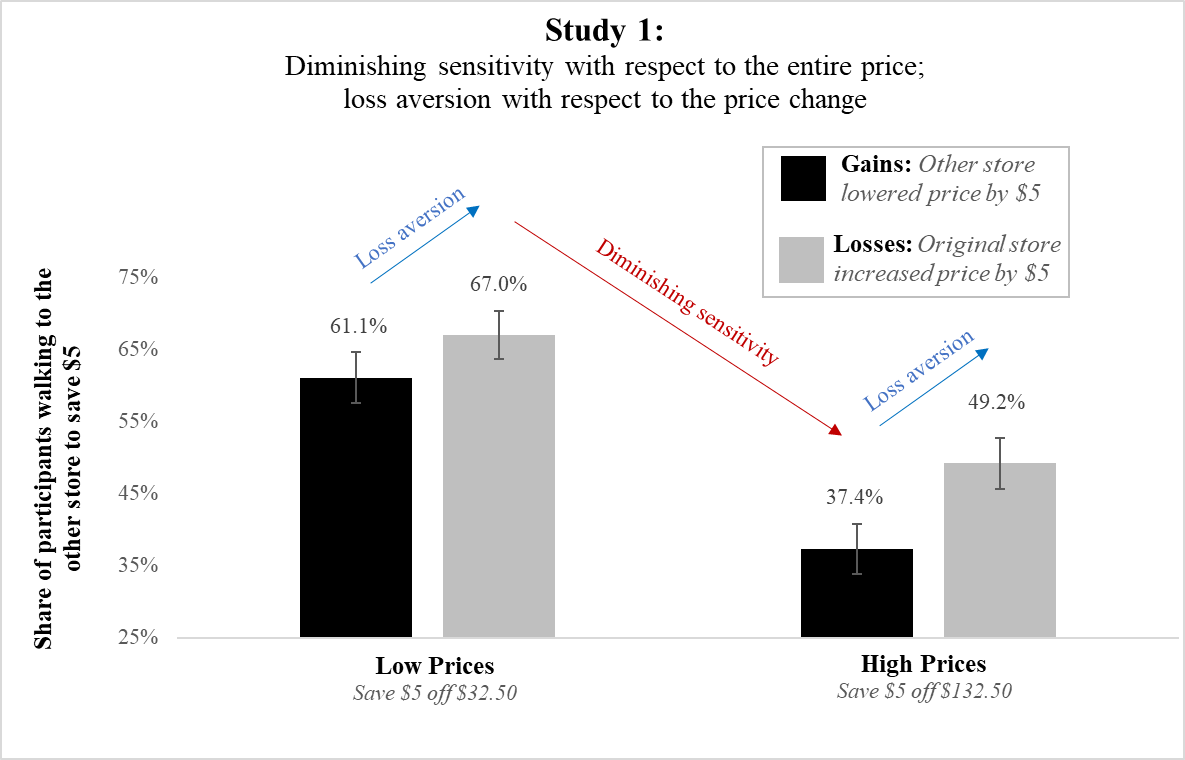

“Diminishing Sensitivity to Outcomes: What Prospect Theory Gets Wrong about Diminishing Sensitivity to Price,” under review at Journal of Marketing Research (with Alex Rees-Jones, Uri Simonsohn, and Joe Simmons).

Question: Why are consumers more sensitive to discounts off of lower prices? Summary (not abstract): People are generally more willing to travel across town to save $5 off a (cheap) $15 purchase rather than to save $5 off an (expensive) $125 purchase. Prospect Theory purports to explain this phenomenon via diminishing sensitivity to losses, but my research suggests that people do not consider these payments to be losses at all. Instead, a $5 gain feels smaller relative to a reference price of $125 than a reference price of $15. Contrary to Prospect Theory, all $5 gains are not the same – and marketers can count on consumers to exhibit diminishing sensitivity to price whether or not they consider their payment to be a loss. |

working papers

|

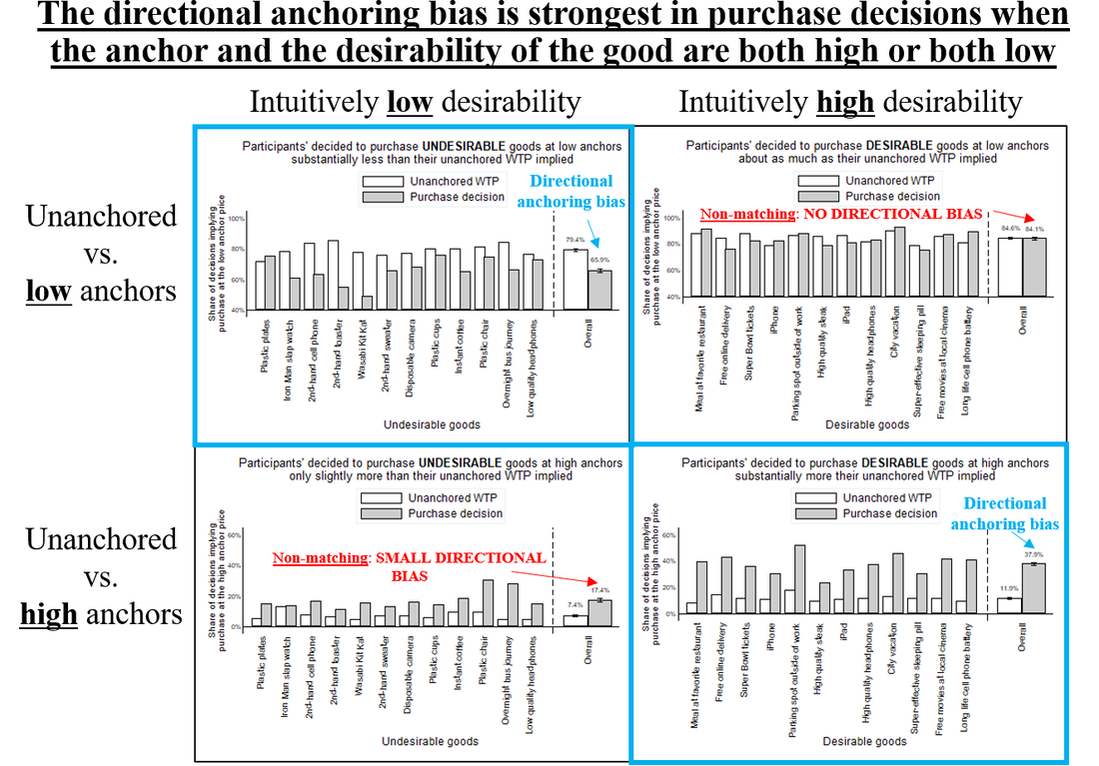

“The Directional Anchoring Bias,” (with Joe Simmons).

Question: Are people too likely to buy high priced goods? Summary (not abstract): Previous research on anchoring effects (wherein people make judgments that are too close to salient-but-irrelevant values, or “anchors”) attribute them to the extent to which people adjust their judgments from these anchors. However, I find that the direction of adjustment is a contributing factor. People are too likely to adjust upwards from high anchors and downwards from low anchors. I also find that prices act as anchors on consumers’ valuations. Consequently, consumers are too likely to buy goods at high prices due to disproportionately adjusting their valuations upwards from these high-price anchors. |

|

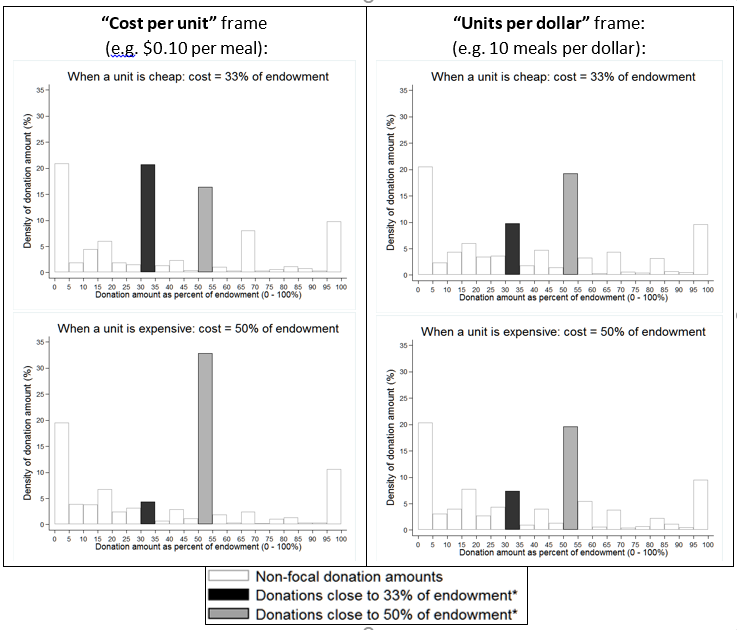

“Ineffective Altruism: Donating Less When Donations Do More Good,” (with Deborah Small).

Question: Do people use information about charitable impact to donate more or less efficiently? Summary (not abstract): When people see cost-effectiveness information about a charitable donation that is framed in terms of “cost per item” (e.g. $2 provides one mosquito net), they inefficiently donate less when the cost is lower. This result arises because people want their donation to have a tangible impact, and when the cost of such an impact is cheaper, people can achieve it with a smaller donation. A remedy for this inefficiency is to express cost-effectiveness in terms of “items per dollar amount” (e.g. 5 nets provided per $10 donated), and leave the cost of providing one net unstated, rendering it less salient as a target donation amount. I am in the process of collecting field data to supplement the existing lab data. |